Text by A.G. Vermouth

Photos by Charlie Eckert

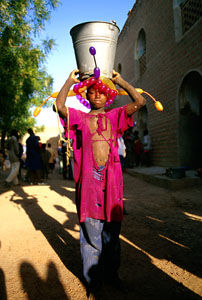

Balloon Hats by Addi Somekh

"Where you going?" the woman asked, standing in the middle of the

street. "You go to Busua?"

"We don't know where we're going. What's Busua?"

"Very beautiful there. My home. I take you there. Follow me."

"Is it on the ocean?"

"Yes. Beach and fishing. Come, follow me."

No arguments there. The four of us climbed into the back seat of a small

Toyota (there were three others in front) and bounced down the dirt road

to Busua, a small fishing village on Ghana's Cape Coast. Toward the end

of the ride, Addi wasn't talking anymore. Charlie wondered whether he was

still conscious, since everyone had been piled on top of him. When we got

out in Busua, Addi explained that he hadn't quite passed out, but that

the weight of everyone's bodies along with the impact of driving through

some large sinkholes in the road had forced all the air from his lungs.

Busua then, not a moment too soon. A balloon hat twister with collapsed

lungs is no one's idea of a party---that is if he actually was what he

claimed to be. Although he had told me three-quarters of his backpack was

full of balloons, I hadn't yet seen one.

The woman led us to her friend Elizabeth's guesthouse, a cement block

structure and some steel-roofed huts around a central court. The sanctuary

of the Musama Disco Christo Church, of which Elizabeth was an elder, formed

the remaining side of the compound. The local children who attempted to

carry, and ended up dragging Charlie and Addi's massive bags seemed confused

that neither one of them was particularly interested in seeing Fort Metal

Cross, one of the sixteen old slave-trading forts that dot the Cape Coast

of Ghana, and the primary reason tourists come to Busua at all. Addi would

merely say, "maybe later," as he and Charlie continued to poke around,

muttering lighting and backdrop logistics to each other.

After dark in our small hut, Addi pulled out some balloons and began

twisting practice shapes for what he knew would be his African debut the

next day.

"You weren't kidding," I remarked as I drew down the holey mosquito

net and began the evening ritual. After a few satisfying kills I sat down

and asked him how he'd picked up his craft.

As he lay on his back, knees bent, with a yellow balloon twisting into

knots over his face, the kerosene lamp on the floor cast giant balloon

shadows on the ceiling, turning the hut into a mad scientist's laboratory.

He described the three months in his bedroom at home, crying over a lost

love, mindlessly twisting balloons to keep his hands occupied---above his

waist. And here he was, probably in the same position he'd held for those

three months learning to twist balloons into sculpture because his grief

would allow nothing else.

Measuring more balloons, he explained he'd been thinking about a new

hat design during the excruciating, six-hour, minibus ride in order to

take his mind off the pain the makeshift wooden seat had given him. More

pain, more balloon hats. This one was turning into a woven web of four

colors as he lay on the cot, squeaking and popping the twists, complaining

about the intense humidity's effects on balloon performance. Laughing children

could now be heard whispering outside the window.

A hard rain came the next day, and not surprisingly "Balloon Hat" (a

new synonym for Charlie and Addi) decided to postpone any performance.

It happened to be Palm Sunday and there were far more than the usual worshippers

in

attendance at the Musama Disco Christo Church just ten feet away from the

damp hut. Throughout the Christian/Animist hybrid rituals of a three-hour

service, village children wearing balloon hats would wander in and out

of the shelter, their hands feeling up and down the contours of elaborate

new headdresses Addi had made for them. Obviously, he hadn't been able

to help himself entirely.

I'd first encountered these two serious young men in the currency exchange

line at the airport in Accra, the capital of Ghana, where Addi just happened

to be standing behind me. I had come to Africa on frequent flyer miles

as part of an egoistic attempt to call myself well-traveled by meeting

Africans and listening to their music firsthand. Wondering whether anyone

else's trip could possibly have been as pathetically half-baked, I asked

Addi what had brought him to the region, expecting to hear that he'd come

for a vaccination project with some Western aid group. Northern Ghana was

in the midst of an unusually harsh meningitis epidemic and the only other

non-Africans on the flight had indeed been Doctors without Borders. Instead,

to my surprise, he hesitated with a sidelong glance as if to prepare himself

for the usual response, and explained that he had come to Africa to make

balloon hats. When I asked him if USAID or the Peace Corps had sanctioned

such an absurd idea, he explained that he and his partner, a photographer

documenting the experience, were financing the project out of their own

pockets. By this time Charlie had arrived with their bags as my night's

worth of money was being counted out under the change window. After a few

pleasantries, I wished both of them luck with an eye-rolling smirk and

disappeared into a chaotic airport crowd expecting never to see them again.

Two days later there they were, though, boarding the same small bus

(known as a tro-tro in Ghana) with the same vague idea of ocean in mind.

I was crushed in next to an officious Ashanti gentleman in a suit and spectacles.

He had spoken at length about his job for a government development agency

and his mandate to find a solution to the problem of street children in

the cities of southern Ghana. Two hours into the trip he stopped talking

and started vomiting into a Notre Dame T-shirt on top of the briefcase

on his lap. My leg was getting the overflow. I glanced back at Charlie

and Addi bouncing miserably in the back seat. The look on Charlie's face

told me he was feeling no less pain than I. A town like Busua couldn't

have been a better place to end such a ride.

Though as is the case almost anywhere Westerners go to try and escape

everyone else of their kind, we soon found we were not the only white folks

around. One walk to the village well revealed two Scotsmen sitting perched

on the stoop outside some random hut, tripping heavily on spacecakes they'd

bought from the local Rasta drummaker. It looked as if the Scotsmen had

set up their new Ghanaian peg drums outside with the intention of practicing

the pa-logo or first rhythm of coastal Ghanaian drumming, but instead had

forgotten who they were, much less why they had come to the village in

the first place. The one thing they probably hadn't forgotten, indeed the

only thing that seems impossible to forget in any altered state of mind,

is that they were in Africa. They had just returned from the Dogon region

of Mali with tales of robbery and harassment, and needed decompression

on the coast before returning home. "We're glad we went and got through

it, but we would never go back."

Though the Scotsmen's stories centered on their difficulties in finding

an honest guide in all of Mali, they also mentioned their planned visit

to Timbuktu, that proverbial most-inaccessible place on earth, had been

thwarted by all manner of obstacle---from thieves in Bandiagara, to warnings

of Tuareg unrest in the region, to lack of any certain overland route---and

they had decided that for them it probably would remain the most inaccessible

place on earth.

Listening with open mouths to the Scotsmen's hallucinatory memories,

Balloon Hat seemed to revel in the sheer happenstance of it all, and right

then under the full moon a tangible goal for their African Balloon Hat

Experience began to rise out of the very thick air.

Timbuktu. Balloon Hat had heard of it before, but where exactly was

it? To discover that it was here in West Africa and perhaps only a thousand

kilometers north gave rise to the quixotic challenge Balloon Hat seems

to need from every journey. An overland dash from a sixteenth-century slave-trading

fort to the edge of the Sahara where exotic hats from the West could be

traded for photos of people rarely seen outside the region; that would

be the easy part. The hard part, all agreed, would be to make it back to

the coast by the next full moon in order to board the nonrefundable flight

out to another part of the world.

The Scotsmen returned to their hallucinations with serious doubts about

the success of such an endeavor. Nonetheless, they smiled at the idea and

wished Balloon Hat luck with eye-twitching smirks.

The Journey

An hour north of Accra, at the southern tip of Lake Volta, the largest

artificial lake in the world, a freight barge christened Buipe Queen makes

its weekly port of call at Akosambo, bringing yams, goats, and other cargo

from the Upper East Region of Ghana to city markets nearer the coast.

The Buipe Queen cruises the lake at around ten knots with a deck full

of empty crates, stopping occasionally to take on cargo and passengers.

During most of the daylight hours no one can move. As is the case every

day in this region, during the high-sun hours people don't talk. Lying

around in empty crates on deck, half-asleep, they rest heads on elbows,

staring sideways into space, knowing they're trapped in a hundred-twenty-degree

floating oven. Even the galley maid who is supposed to be on shift cannot

help but pass out over her counter. If anybody wants to eat, they have

to be satisfied only thinking about it. But then as simultaneously as any

African town seems to awaken itself, people stir a bit all at once---maybe

think about moving for some bit of sustenance---and the late afternoon

comes alive with conversation and a new shift of work for the crew.

It was here among swarms of lake flies too numerous to swat that I asked

Charlie how he happened to find himself sleeping on tables and cement floors

halfway across the world for the dubious privilege of shooting photos of

people in balloon hats. His answer was simple. To see the look on a child's

face, to discover people's universal need to laugh, to find the connection

to humankind strengthened by the smallest gift of color, had become more

than addictive. It had become his only purpose.

He said he'd first noticed people's reactions to Addi's hats on a Halloween

night in New York the previous year. After a group of four of them had

failed to come up with any costumes for a friend's party, Addi, who was

then only a vague acquaintance, offered to make hats for all of them and

fulfill the costume requirement without too much work. The moment they

stepped onto the street, though, Charlie was amazed at the awe-struck responses

to the hats. He had walked these streets his whole life without so much

as drawing a glance, and here were total strangers smiling, laughing, eager

to converse. The next morning, hungover at the breakfast table, he wondered

aloud to Addi whether taking the hats to people all over the world might

be a cool thing to do. He hadn't quite realized how seriously Addi had

taken him until a couple weeks later when Addi called and told him he'd

cleared his schedule and was ready to begin the project.

Now here he was, in the middle of the hot season in West Africa, lying

on top of a table with flies stuck to his face, wondering when the cool

part of the idea would occur to him again.

Thirty-two hours after the Buipe Queen's departure, Balloon Hat and

I debarked from the freighter on Lake Volta's northern shore, where there

still remained another twenty-four hours of almost continuous travel by

dump truck, minibus, and small, beaten sedan before reaching Bolgatonga,

the capital of Ghana's Upper East Region. In Bolga, we could rest for a

day or two and figure out the shortest way across the border to Ouagadougou,

the capital of Burkina Faso, and from there into Mali, and with luck, Timbuktu.

Mad Dogs and Balloonhatmen

Solomon, our local man in Bolga, actually a seventeen-year-old on break

from the Navrango Secondary School who had marked us getting off the dusty

bus, magnanimously offered to act as guide to the nearby village of his

birth.

In a rented yellow Toyota, Solomon brought us five clicks on a dirt

road southwest of town where we parked underneath a lone Baobab tree, looking

beyond a few goats to a settlement of painted adobe huts well away from

the road. The inhabitants could not have known what awaited them. Nor could

Solomon for that matter.

Laboring with bags of cameras and balloons over dusty, cracked earth

in the heat of another hundred-ten-degree day, Charlie noticed Addi had

forgotten to bring his hat. He walked up next to him and asked how he was

feeling.

"Nauseous. Dizzy. I might pass out." Addi had been vomiting and feverish

since the previous evening's arrival in Bolga. And though none of us could

utter the word, some strain of malaria seemed a likely scenario in our

paranoid white people's minds. Of course it turned out to be his anti-malarial

medicine, but that would take another few weeks to understand.

"Can you make any hats?" To that Addi gave a look of hopelessness, knowing

he could do nothing else now that he had come this far.

He lasted for a respectable five or six hats before turning to a bizarre

shade of off-white, and back in the car he explained that he had basically

gone on autopilot---blow and twist, blow and twist---and at the moment

didn't know whether he would even be able to get out of the car at the

next stop. But during the short drive to the next settlement, as Charlie

mentioned the approach of near-perfect, late afternoon light---the golden

time---Addi knew he would have to drag himself out of the car again and

somehow manage to keep going until the sun was gone.

At the next settlement Charlie entered a frenzy of shooting unlike any

before it. The sun was low, truly gold, enhanced by the reddish dust of

the earth in the region. The sky was perfect too---a brilliant blue with

giant cumulus clouds adding depth to the scene---a landscape completely

different from that of the jungles of coastal Ghana. The Balloon Hat had

reached the edge of the Sahel, the great buffer zone between the ever-expanding

Sahara Desert to the north and the rainforests of equatorial Africa to

the south. And Charlie was, without question, trancing to the light's effects.

He continued shooting long after Addi had stumbled back to the car, waiting

in the back seat to die.

On the way back to Bolga as Addi hung his head out the window, our driver

swerved to avoid a stray dog in the middle of the road. Solomon seemed

strangely disappointed in this. A moment later he casually mentioned that

both the Dagete and Grune people of Northern Ghana like to eat dogmeat.

According to Solomon, they not only like the taste of it, but they also

believe a man will die at home rather than during his travels if he eats

the sacred flesh of a dog raised for this specific purpose. As Addi

seemed to be getting sicker by the hour, it was unanimously decided that

a dose of dog from the new market in Bolgatonga might be the only way to

get him back to the States intact.

The new market is a place where men buy and sell goat kids and black

and white checkered guinea fowl, or sit under corrugated steel-roofed shelters

drinking pito, a sour, fermented millet wine, out of large calabash bowls

as they recline and listen to the spare sounds of lute and shaker.

Over in the dogmeat shelter six men sat in a row at a wooden table,

whiling away the afternoon, eating chunks of dog sprinkled with hot red

pepper freshly crushed in a nearby mortar and pestle. Solomon suggested

buying a thousand cedi's, or about sixty cent's worth of meat and choice

organ slices to make enough for everyone back at the hotel. There can be

no doubt as to the animal it has come from either. The butcher leaves the

leg and rear paw on the boiled meat, and unmistakable jawbones lay strewn

on the ground beneath the table seeming to say "You've tried the rest,

now try the best."

A thousand cedi's worth turned out to be over a pound of flesh. It seemed

much of it would be wasted.

Back at the hotel the meat was spread out on a night table, and inspection

began. As I was reading a particularly interesting piece of liver, Solomon's

fingers grabbed it and popped it in his mouth. It became apparent then

that if Addi didn't rise up from his deathbed soon for a piece to chew

on, Solomon would eat the entire pound, compulsively, like snack food,

leaving nothing for the cure. Eventually, with some prodding, Addi forced

a couple pieces down and fell back hard on the bed.

Five days into the journey here, we could only worry that if the illness

didn't suddenly improve, his life would possibly be in danger, making the

goal of Timbuktu unattainable. Fortunate then that Ouagadougou, the capital

of Burkina Faso, happened to be the closest city with any substantial medical

facility and also happened to be on the way to Timbuktu. Addi basically

had no other choice but to press on and make the dusty four-hour ride by

broken dirt road through a desolate border zone, putting us that much closer

to the goal, whether the dogmeat ultimately succeeded or failed to do its

job.

A Colonial Façade

Addi seemed to be about as bad off as the rest of us---certainly no less

alive---when we eventually found our way to the outdoor bar of a French-owned,

jungle-style hotel in Ouaga where there was red wine and warm goat cheese

salad and pastis. We dined with a thirty-year-old, Doctors without Borders

worker who considered West Africa the premier region on the continent for

partying after long stints in war-torn countries like Burundi from whence

he'd just arrived. A stopover on a flight to Paris had brought him to Ouaga

for a weekend of drinking and paid sex, after which he would decompress

at home for a week, pick up his surfboard and return to West Africa for

a new six-month mission in Liberia where the surf is reputed to be some

of the "most killer" in Africa. Although he claimed the surf was what had

ultimately drawn him into his sixth mission for the organization, it was

clear his drink was doing the real talking. He stared far into space as

he summoned the words to explain how each time he finishes a stint he assumes

will be his last, someone in Paris calls and drops the name of yet another

war-ravaged African country in his ear. "It is like a disease, you know."

It was clear he was never going home again.

According to "Frenchboy," in Ouaga prostitutes cost 5,000 CFA, or around

ten dollars, for an entire night. This is, of course, best price, and must

be bargained for. His own companion for the evening was a tall, urbane

and jaded-looking, high-cheekboned woman in an exceptionally fine red evening

dress. She looked strangely fitting at a table among the T-shirts and unshaven

faces of male aid workers.

After I had decided to retire for the night I remembered having about

seventy French francs in coin left from a stopover in Paris. Since Frenchboy

was returning to Paris for a week the following day, I decided to give

him the money. When I returned to the bar to offer it to him, he protested

loudly and began to cry. I stressed that I would not be going back through

Paris anytime soon and that he should have some fun before returning to

Liberia. His emotional outpouring over a gift of what amounted to no more

than twenty dollars perhaps stemmed from the heavy stress of a life witnessing

human atrocities almost daily, dotted with sporadic urban pleasures like

the hotel in Ouaga. In a fit of inspiration his eyes brightened and he

asked me my plans for the evening. When I told him nothing much and that

I was ready for bed, he offered his woman to me. "It will be my pleasure.

We will drink and dance in the after-hours clubs." I thanked him no, finished

my pastis, and retreated to the room where Balloon Hat was snoring loudly,

and the air smelled of ninety percent DEET.

Wading through this busy city to find the shortest way into Mali, the

Balloon Hat found numerous obstacles, the only direct road being a sand

track through the long border zone, rendering any organized bus travel

impossible. A high clearance, four-wheel drive vehicle was needed because

no one could vouch for the existence of a continuous road, much less it's

traveling condition. There were now entire days devoted to figuring out

where to find such a vehicle and how to afford it, and if it even remained

possible to reach Timbuktu or any of the other ancient trading towns along

the delta in an ever-shrinking window of time.

Sitting on the stoop of our hut almost a week after arrival, just when

all energies had given way to isolated frustration---Charlie immersed in

The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath and Addi studying the vascular parts of a

rabbit from a stew he had decided not to eat---a random connection suddenly

panned out. A colleague of a friend of a cousin of a man who had been amused

by the balloon hats during a small market performance found it in his heart

to secure our passage into Mali on a Mission Order with the Ouagadougou-based

Association of African Solidarite. The mission's purpose: to travel unhindered

by politics, promoting AIDS awareness in the villages of the Niger River

Delta of Mali. Apparently the balloon hats had reminded the Association's

president enough of the potential festivity of condom use that he agreed

to provide a jacked-up sedan of otherwise questionable mechanical condition

for a trip through the Delta region and into the remote villages on the

way.

Along with the car came a twenty-year-old driver named Noufou who seemed

to owe some kind of favor to the Association. The trip would be rough-going,

and it was apparent from the outset that Noufou would much rather have

been sitting on a street corner in Ouaga than driving his first trip ever

out of his country. In fact, Noufou turned out not to have any of the proper

papers for such a job, and the Balloon Hat, far from being protected by

the Mission Order from bribes and other border snafus, was continually

hit up for various sums of money because of Noufou's lack of credentials.

Even at the first checkpoint just outside Ouaga, our man with the badge

decided to levy a fine for all vehicles carrying hazardous materials like

gas and oil on the district's roadways. It was either pay him right then

or be detained by romantic kerosene lamplight for hours or even days. So

much for international cooperation. In Africa, the white man travels with

a large dollar sign pasted to his forehead.

Frontiers without Games

Somewhere in the middle of the hot and dead border zone between Burkina

and Mali, Noufou's post-apocalyptic driving habits gave way to the first

blown-out tire of the journey. The sand track had suddenly become passable

only on camelback and our old sedan had bogged down in the depth of a shifted

dune. At the same moment, a young boy tending a few goats far across the

dry scrub ran shouting and waving at the car, warning us of the danger

we had already encountered. With his guidance we were able to push the

hobbled sedan up unto the scrub and over to a small encampment where the

car rolled to a stop among a dozen huts and fast became surrounded by every

one of the inhabitants within sight.

One of them, a well-kept young man wearing a clean white T-shirt, was

deferred to as liaison for the practical reason that he was the only one

present who could speak any French. Only up to ten percent of Mali's population

actually speak this official language, and it is of course the citizens

who've had the most contact with outsiders who make up that ten percent.

Whether the literal heat of the moment or some recent interaction in the

city was to blame, "White Shirt" fast became interested only in what monetary

advantage could be gained over the Balloon Hat.

As Noufou attempted to use a broken jack to raise the car, Addi decided

to tie his apron around his waist and blow up a few hats---take his mind

off the quickly worsening problem of a break down in the middle of nowhere

rather than panic his way through an afternoon. Charlie had no such luxury

as good portrait photos require much more of a kind connection to the subject

in the viewfinder. Where Addi can disarm the potential enemy with the magic

in his hand, Charlie must engage and win a person over through a sensitive

and conciliatory demeanor designed to dissolve the metal barrier of the

camera.

Noufou, cursing the broken jack and unaware of the rising tensions for

money, asked fifteen villagers to lift the car so he could change the tire.

White Shirt happened to be busy at the moment arguing angrily with Charlie

over the price of a photo. The other villagers had become entranced by

Addi's balloon-twisting and could not understand the hard feelings being

generated by such an amusing situation. But White Shirt was relentless,

bent on convincing the group not to be entertained by such opportunists

stealing images of Africans. White Shirt's hostility toward the Balloon

Hat had fast come to the point where a "Plan B - quick escape" needed consideration.

Charlie, simply by holding a camera, had become the embodiment of patronizing

Western arrogance, and was being surrounded by ever more villagers as White

Shirt continued his diatribe in the local language. At that moment, Noufou

was just finishing with the tire and suddenly began to understand

the urgency of the situation. He jumped behind the wheel and summoned the

Balloon Hat to get in quickly.

Strange to have an entire village fascinated by the absurd arrival of

a beige Toyota being pushed by men with balloons, only to have the ad-hoc

leader of the group take it for what it could only be in any cynic's mind:

a financial opportunity. Of course this is just what the Balloon Hat is

banking on by traveling around the world on its shoestring budget---the

eventual book deal and its potentially lucrative merchandising tie-ins.

If only we could have sipped these pure and sweet ironies of the road like

water, there would have been no need for the expensive Swiss filter, and

no cause for all the parasites we received anyway.

What Façade?

Charlie and Addi sat in the back seat of the old Toyota, wondering why

they had urged each other to come this far. The afternoon was already half

over, and no one yet knew where we would be able to stop for the night.

Noufou had effectively taken the project hostage and spoke only when asking

for another cigarette. Only the bouncing of the ride could vent the rage

toward him and all of Africa at that moment, whether misplaced or not,

for having caused the situation at hand. A dark grey band of sky began

to grow from the North looking like heavy rains coming to turn the red

sand of the track to impassable mud. No one could have felt lower. Noufou

gestured his head toward the sky. I nodded and looked back to Balloon Hat

stewing in the back seat and noticed that both Addi and Charlie had become

transfixed by something out the opposite side of the car. We had been traveling

now for an hour with the cliffs of the Bandiagara Escarpment on view out

the right side. As the car approached the western end of this two-hundred-foot

red wall, the Balloon Hat spied three Tuareg shepherds walking their flock

along the base of the ridge. They looked at each other when Charlie let

out the low, open-mouthed laugh of amazement at what he was seeing, saying,

"this is it," with only a smile opening his mouth even further. Noufou

failed to notice the flock, concentrating instead on the middle of his

cigarette and the holes of road ahead. After perhaps four attempts at saying

"stop" to get him out of his road trance, he awoke and began to slow the

car down.

"But why?" he asked, as Addi bounded out of the still-moving car and

ran across the red dust a hundred yards with the denim apron of balloons

in his hand. Charlie followed fast. Noufou sat at the wheel shaking his

head with disdain.

"Those men are bearded men. It is not good. They do not want an intrusion.

Dangerous. They use their knives to chase your friends away."

Addi was already in the middle of the first hat for the oldest in the

group, a small man dressed in the rich blue tunic of the Sahel, when Noufou

decided it was safe enough to get out of the car himself. The shepherd

was staring at the balloons with a half-smile, happy to break up his day

of herding with such a strange entertainment. Now and then he and the others

would glance ahead to their flock receding in the distance, careful not

to lose them from sight but far too intrigued with these strange fools

in the middle of nowhere to leave the scene. No words were spoken between

the two parties. None were needed. A connection had been made and the Balloon

Hat could not offer enough thanks to the shepherds for turning this miserable

day to ecstasy. With thanks by way of handshakes, the shepherds took their

leave, holding hands to hats as they ran to catch up to the flock, now

almost a half mile down the ridge.

The thick grey wall in the sky was coming closer as the car climbed

up the switchbacks over the ridge. At the top was an encampment of no more

than five or six stone huts. This time Noufou stopped the car without asking,

and everybody piled out without discussion.

First, the bearded one---white cap, the elder. The grey wall was almost

to the bottom of the ridge, rolling in at gale force. Not much time then,

everyone could see---maybe time for one or two more hats. With a glance

to the horizon, the elder chose the smallest boy, the only completely naked

person in the group, to receive the last hat. The little boy was dazed

at the sight and thought of what had just entered his life. And then for

the test, the all-important photo, he covered his penis with shrewd modesty,

only to be cajoled to uncover for the camera by the fifteen men around

him. He complied slowly, as everyone else let out hearty laughs. And then

the first gust arrived, setting us all on edge. It turned out not to be

rain, but dust---the harmattan from the north come late for its season,

and the storm was just beginning. Running for shelter and the car, both

groups had only enough time then to wave. There was a truth in that moment

though---a simple, wordless connection between two disparate peoples and

the realization that all was suddenly and ultimately under nature's serious

command.

For the next hour, driving through the 100-foot-deep canyon that is

the roadbed to Somadougou, a Tuareg hitchhiker was squeezed into the back

seat with the Balloon Hat. Charlie stared dumbfounded as the nomad lifted

his long blue sleeve to reveal an identical wristwatch. Addi was also silent,

having just experienced the entire reason for leaving the comfort of his

room at home. Noufou, for the first time in his life, was gaping at the

major rock formations surrounding him. He had forgotten he was driving,

and---with only the Tuareg's urgent yell as warning---barely managed to

swerve the car around a place where half the road had fallen away into

the bottom of the canyon. Nervous laughter was all the gall anyone could

give him, though. It was too close for anything else.

That night under the stars on the roof of Sofara's mosque, a crescent

moon, the Pleiades, and Comet Hale-Bopp, arranged themselves in a triangle.

The comet seemed to shift from red to blue and back to red again. The Balloon

Hat felt life, and sleep was very sweet on old straw mattresses.

Ignorance is not Bliss

The feeling did not last long. The next afternoon, in Djenne, another ancient

trading town wrecked (I mean, I don't know why I say wrecked because there

are a lot of PC efforts that are cool and have done good things, in terms

of whatever good we're talking about) by a comprehensive Peace Corps effort,

we sat half-comatose in a hundred-ten-degree mud hut on another roof, wondering

how much worse the road conditions might get further into the desert. Our

jacked-up sedan had barely gotten us this far, and the only other vehicles

seen since the border had been donkeys, camels, and the occasional fully-geared

Rover.

Strains of a short wave radio broadcast wafted up from the courtyard

below where Allaye, our host, boiled down the afternoon tea over his small

coal fire. Hearing the word "Timbuktu," Balloon Hat stumbled down the steps

leading off the roof to catch the tail end of a report that three French

travelers had been shot by Tuareg separatists on the track just outside

the town. Noufou's initial fear of the shepherds at the escarpment came

to mind. Would the Tuaregs act any differently toward Americans pulling

balloons out of thin air? We sat silent, hot, and wondering until the next

morning when it was decided that the decision could be put off even longer

by embarking on a short backtrack to visit one or two of the unmapped villages

we'd missed toward the end of the escarpment.

About 6 clicks back in on the red dirt track, the Toyota's already woefully-patched

radiator began steaming badly. A lift of the hood revealed that the fan

had also stopped working. We all stood around the engine gaping at the

pile of junk that had actually brought us this far. Mechanical failure.

Good thing too, because nobody here---not even Noufou---could be blamed

for this one. The lingering question of the previous afternoon had ceased

to matter. Balloon Hat would not reach the end of the earth. Any attempt

to continue north into the desert at this point would have proven beyond

mere artistic insanity full into the realm of stupidity.

Brown Acid

Nothing to do next but send Noufou with the car back to the nearest town

for some jury-rigging to get us back to Ouagadougou. Agreeing to meet him

at a crossroads before sunset, Balloon Hat decided to search the track

for a nearby settlement to visit---try to make some sense of an afternoon

that had brought the failure of an entire trip down to bear on the collective

conscience.

A few steps around the first bend in the road, there was a stone wall.

Twenty steps later, a gaze through the slats of a closed wooden gate in

the wall revealed a village full of small dried mud huts on piled stone

foundations. The huts wound all the way up a steep, rocky hillside cut

with narrow switchback paths. No people were visible.

"Is this it? Where is everybody?" Charlie asked.

"This looks like the place, probably the only place around anyway,"

Addi said, pulling out a pineapple he'd carried all the way from Ouaga.

We sat down on the roadside and began cutting the pineapple into slices,

discouraged and wondering how to make balloon hats for an empty village.

Ten minutes later a lone figure became visible down the road, and slowly

turned into a small man on a donkey returning to the village from some

long errand. He stopped his ass in front of us and stared down silently.

Charlie offered him some pineapple while Addi pulled out the balloons and

started in on a hat. Within another two minutes, fifteen villagers had

appeared out of nowhere to surround the Balloon Hat just as Addi was crowning

the "Donkeyman." The man seemed to take this as some kind of sign and immediately

ordered the gate opened for our entrance. No words were spoken and there

were no smiles forthcoming, so it was impossible to tell exactly what his

intentions might have been.

Addi went first, as the hat can precede any explanation, and was quickly

swallowed up by a crowd of villagers ushering him up one of the mazelike

paths. There were now swarms of people around Charlie also, curious to

get a close-up look at a person with blond hair and blue eyes. The camera

had suddenly turned back on him in the form of some fifty eyes, and he

could only imagine what strangeness could be held behind the gate. With

mounting concern he passed through, calling Addi's name while the crowd

looked on, trying to decipher his urgent entreaties.

"Oh no, I think they're beating him to death!" Charlie shouted, looking

up the hill to a group of villagers violently thrashing something unseen

on the ground with large wooden clubs.

Although it was most certainly a ritual we had seen in other villages in the region,

at the moment, anything did seem feasible in the sudden chaos

that had enveloped us. So we climbed fast up one of the paths to get a

better look, and continued shouting after Addi.

With bemused expressions, the crowd ushered us ever further up the paths

past old women in the shade preparing food and young men in the sun doing

nothing, until we had reached the elders' hut on top of the cliff with

half the village in tow. Addi appeared from another path followed by the

rest of the village, and the two crowds merged here to from one giant mob

of elated, spontaneous celebration. There was relative peace inside the

elders' hut where seven bearded men lay on goatskin rugs and received us

warmly with offers of tea and bread. It was only a matter of minutes, though,

before twenty villagers had forced themselves into the room, beyond the

bounds of village propriety, with a single urgent demand for balloon hats.

The chief continued to be amused, but when the chaos had proved too much

for the small space, he ordered everyone outside with his big stick and

his highest voice.

The celebration rose to new heights on the cliff where Charlie began

shooting a small boy in balloon hat performing a smallboy dance for what

had now become the entire village. Seeing the immense joy Balloon Hat had

brought to his people, and realizing by then that the only way to avoid

a large-scale riot would be to take the heat off himself by pressing Balloon

Hat's hand, the chief spoke up smiling and said, "Certainly you will sleep

here with us, yes?"

The villagers cheered in agreement.

"Uh, we have to get back to our car in Somadougou before dark. Our driver

is fixing it there." Addi said, shifting his eyes back and forth with what

could only have been noted as...confusion. The chief of course could not

understand a word he was saying, so he smiled some more as more balloons

were pulled out in a futile attempt to control some of the chaos. At that

moment Addi looked down at Charlie, content behind his camera, and around

at the hundred people clamoring for his attentions. Charlie turned then

for no known reason and shouted, "I think we accidentally took the brown

acid today!" before just as quickly returning to the boy in his viewfinder.

"How do we get out? Too chaotic, " Addi stuttered into the din of the

crowd. Charlie could not hear him.

Time stopped briefly then as Addi held a hand to his head, and it became

abundantly clear that with Donkeyman's invitation to pass through the well-guarded

gate of the village, Balloon Hat had indeed passed through a kind of shortcut

portal to a another civilization, a place without Coca-Cola, a culture

that had held fast to its original way by shunning the tourism that had

invaded the rest of the region.

At that moment Timbuktu had ceased to matter. After all the heat, sickness,

and dust of the road, the Balloon Hat Experience was melding, albeit chaotically,

with some dumbass explorer's idyllic vision of Africa, and the goods had

been delivered. Balloon Hat could only hope that the laughter and unity

it had inspired here would be the only lasting effect of its visit after

all the balloon hats had popped or deflated. But, having come back through

many of the same towns on our way back to the coast and hearing tales from

other travelers about the Balloon Hat, one does wonder whether the next

white person who somehow happens upon this place or any of the other unmapped

settlements off the track from Bandiagara to Somadougou will be presented

with a wilted crown of balloons to make whole again, and what he will do

in response. Rather like in the continuing aftermath of the colonial presences

in West Africa, another one of the numerous aid groups appears to fill

some perceived vacuum of need with a specific mission of its own, and instead

finds itself being repeatedly asked for biscuits or soccer balls.

As even a Western-educated Ouagadougou professor asked us rhetorically:

"What could be good about some European standing on the side of a road

urging you to come have a needle put into your arm? We are born in Africa,

we live our entire lives in Africa, and we will die here. What else matters?"

Back in Accra, Balloon Hat sat under shade on a street corner, unshaven

and gaunt, eating fried plantains. A couple of white Europeans passed by

walking tall in the midday sun, carrying brand new daypacks and water bottles

on their hips. The Balloon Hat looked at itself, shaking heads and smiling.

It might just as well have been looking in the mirror five weeks before. |