The Fragonard Paintings of Louveciennes

|

|

|

|

|

The Pursuit (1)

|

The Meeting (2)

|

Love Letters (3)

|

The Lover Crowned (4)

|

Madame Du Barry commissioned Fragonard to paint four tableaux to

decorate her new pavillon but they were displayed only a short time,

ending up eventually in the Frick Museum in New York City where they can

be seen today. More Fragonard

The restored Du Barry pavilion has reproductions of the paintings

displayed in the north-west

corner room

. Did they get installed where they had originally

been intended to go? Several scholars analyze the placements differently.

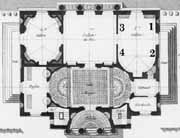

Mary D. Sheriff, in her book Fragonard Art and Eroticism, cites work by Sauerlander who places the paintings (keyed as above) in these locations in the salon on the opposite side of the central Sallon du Roi:

Excerpts from lecture notes by John D. Tatter, Birmingham-Southern College, jtatter@bsc.edu

entitled:

Satiric and Social Painting

Hogarth, Watteau, and Fragonard

The Progress of Love is a series or collection of four paintings designed for the walls of one of the two salons in the chateau [really the pavillon ed.] of Louveciennes, being remodeled for Mme Du Barry, the king's mistress, in the early 1770s. Rather than a sequence, the four seem to be an ensemble that depicts four facets of love. The collection is not original in concept, and it grew out of the tradition of Watteau's fêtes galantes earlier in the century and from the pastoral paintings of François Boucher. Boucher's pastorals were representations of the pantomime theatre, and they were primarily static and bucolic. Fragonard's episodes are full of action in the same way Watteau's fêtes galantes are, but with an added element of poses drawn from classical ballet.

- Storming the Citadel or The Surprise or The Meeting (1773)

- This picture depicts the two lovers bathed in an almost unnatural radiance of stage lighting, and the woman's gestures derive directly from the stage. The thrust of her hand against the greenery is mirrored in countless prints of the period depicting dancers or actresses directing the audience's attention to the wings: this was a pantomimic gesture gaining popularity in the French theatre at the time.

Besides the dramatic tension between the two lovers, however, there is a tension between them and the sculpture that towers above them--a statue of Venus withholding Cupid's quiver of arrows from him. Watteau had used a different version of this sculpture in at least two of his paintings, and Fragonard would have known those paintings as well as Dryden knew Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra. In Watteau's paintings, however, Venus is playful and smiling. Here she is rough and menacing, almost knocking Cupid off of the cloud. The trees in the background, too, seem to shy away from her and match the angles formed by her body and Cupid's. You might be reminded of Pope's line in "Windsor Forest" about Nature there: "Not Chaos-like together crush'd and bruis'd, / But as the World, harmoniously confus'd."

- The Declaration of Love (1773)

- The calmest work of the four, this picture has a statue of Venus as friendship dominating the scene at the right. The lovers in the center act almost as a human sculpture, the woman on the central pedestal and the man leaning into her shoulder in a stylized posture of devotion. If these postures seem overly artificial to you, it might do to remember that adolescents today often mimic the walk, the talk, the gestures, the hairstyles, and the clothing of movie and television stars, and that if the young men and especially the women of Fragonard's day mimicked the gestures of the Belles of the theatre in Paris it should not be surprising. This painting, at any rate, would not have seemed unduly artificial to a contemporary viewer any more than an Olan Mills portrait, complete with artificial countryside background seems inappropriate for the wall of your parents' home. You might also notice here that the trees create the shape of a heart behind the couple.

- The Pursuit (1773)

- In this picture the woman is again in motion, and to a contemporary viewer she would have been unmistakably performing in a ballet. She is leaping in a classic ballet position, and she wears soft, low-heeled ballet slippers like those worn by professional dancers of the time. The grouping of the three women is also a direct allusion to a contemporary choreographer's typical composition of figures on stage. In a similar way, the sculpture in the upper right of Cupids with a dolphin fountain would be recognizable as a visual allusion to Boucher, who often included such sculptures in his paintings, though with a much lighter and playful touch. Here, as in the first painting, the sculpture suggests darkness and turbulence, or at least mystery. Love may be a game with a conventional ending, but in the middle of the game convention dictates suspense.

- The Lover Crowned (1773)

- Along with the sorts of details you see in the companion paintings, here you will find scattered attributes of the sister arts, particularly the lute and tambourine and the sheet music, but also the statuary, the architecture, the landscape garden design, and the implied allusion to the dance and the opera and, therefore, to literature. Note also the presence of the artist himself in the figure in the foreground, who by his posture initiates the diagonal movement of the viewer's eye first to the woman's head and then on up to the statue of the sleeping Cupid. It is not the actions of the god of love now that animate the scene but the actions of the painter. Notice that in all of these paintings the gardens depicted are as lush and overgrown as the landscape on the island of Cytheria in Watteau's painting. But also notice in this picture that two of the plants are orange trees growing in large boxes, natural and artificial at once. In order to produce oranges without damage from the cold weather, orange trees were planted this way to be moved inside hothouses called orangeries. The figures in these paintings are hothouse plants of a different sort, as protected by their social class from the wildness of life as Pope's shepherds are by his poetic composition.

I would also like you to consider in more detail the relationship between the human figures and the sculptures depicted in the paintings. Normally we think of sculpture as static and eternal. When we come upon it in life, we know that it has appeared the way it has for a long time. In these paintings it is used as commentary on the action, and it serves as a response to or illustration of the lovers. The painter has created both at once, however, so the illusion of the sculpture's permanence versus the lovers' temporality is an illusion. Because they are created artificially in the painting, they are as permanent/eternal as the staturary. And perhaps the scenes they depict are just as eternal.

John D. Tatter, Birmingham-Southern College, jtatter@bsc.edu